In our previous post we showed the hypertext version of the Bloom filter interactive tutorial shipped with our prototype library PharoPDS.

Let us now a brief digression about our motivations for writing this small library or, more precisely, about the approach we followed for developing that library.

Two traditions of computation

What computers are for?

This is a fundamental question for the software development field because its answers have determined the nature of the computer artifacts we have built in the past, from the computers themselves to operating systems, programming languages, software tools, user interfaces, etc. The answer to this question will continue inspiring the building of software systems and their role in the society. Our answer —as civilization— to this question will shape our future in an hypothetical continuum from the technology alienating dystopia to the technology enabling utopia.

Historically we can distinguish two different visions or models of computation trying to give answer to the previous question. The dominant vision has always considered computers as number-crunching machines used to speed up calculations. Michael Nielsen refers to this model in his essay Thought as Technology as the outsourcing cognition model:

A common informal model of augmentation is what we may call the cognitive outsourcing model: we specify a problem, send it to our device, which solves the problem, perhaps in a way we-the-user don’t understand, and sends back a solution.

In the 1950s an alternative model began to develop and Douglas Engelbart published the vision in his 1962 paper Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework. He intended to augment human intellect, that is to boost collective intelligence and enable knowledge workers to think in powerful new ways, to collectively solve urgent global problems.

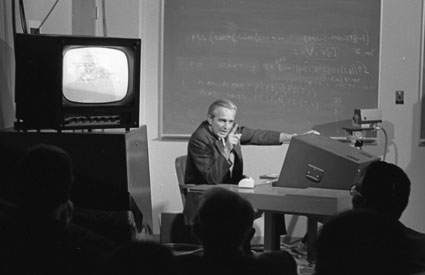

Doug Engelbart during the known as mother of all demos in 1968

The work of Douglas Engelbart, and other designers like Ivan Sutherland (Sketchpad), J.C.R. Licklider (Intergalactic Computer Network) or Alan Kay (Dynabook, OOP and Smalltalk) conformed a vision where computers weren’t mere super-fast calculating machines, but joyful machines: “tools that will serve as new media of expression and inspiration to creativity”. After this vision computers are a mean to change and expand human thought itself. Tools that humans should use to expand their own capabilities, i.e. human intelligence augmentation.

We can trace both models back to the early years of the first electronic computers. However, the struggle between these two worlds is still present today. For instance, Intelligence Augmentation (IA), is all about empowering humans with tools that make them more capable and more intelligent, while Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been about removing humans fully from the loop. You can read an excellent essay (Shan Carter and Michael Nielsen) about this topic.

We can also follow the tension between both forces in any computer-related technology, from programming languages to software libraries. For instance, the design principales behind Smalltalk include, among others, the following:

- Personal Mastery: If a system is to serve the creative spirit, it must be entirely comprehensible to a single individual.

- Purpose of Language: To provide a framework for communication.

The design of Smalltalk (and languages, like Pharo, heavily inspired in it) is clearly commited with the Engelbart’s augmentation vision. We invite you to examine the design principles of your programming language, if such a thing even exists.

Constructivism and microworlds in software development

We consider that the intelligent augmentation vision has never been the dominant model. However, it has strongly influenced a lot of researchers, like the computer scientist and educator Seymour Papert.

Seymour Papert published Mindstorms in 1980, in which he conveyed a vision for how to leverage the democratization of computing for learning.

Papert’s work on the Logo programming language and his concept of microworlds as a learning tool were based in the philosophy of constructivism.

Constructivism is the name of a school of educational philosophy closely aligned with the theories of psychologist Jean Piaget. Essentially it consists of the idea that learning involves individual constructions of knowledge.

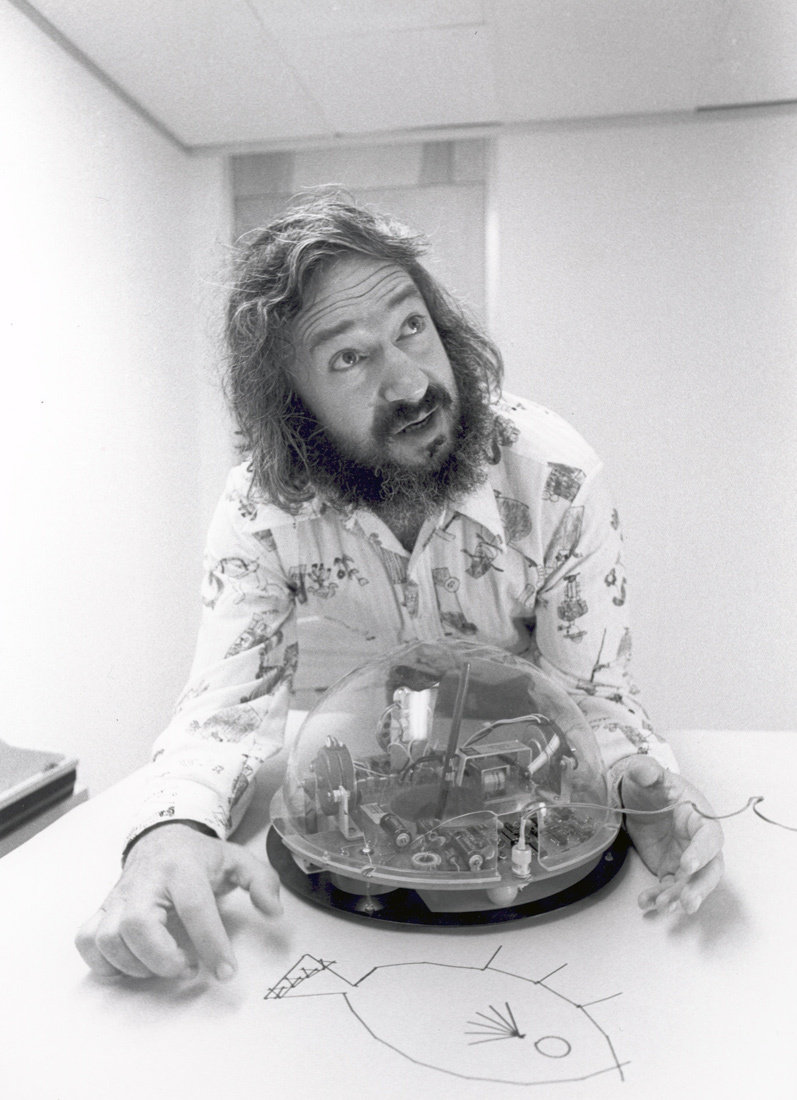

Dr. Seymour Papert with the robotic Logo turtle.

Papert argued that you didn’t learn concepts by absorbing them directly into your mind, but rather, you had to develop your own personal understanding of the concept’s meaning by building upon your prior knowledge.

You may remember sitting in a class trying to get an intuitive sense of a new concept, but only having your aha moment when you found the right insight of the idea, probably through a non-formal representation, that was deeply connected to something you already understood.

We agree with Papert’s view of knowledge as individually constructed. We also agree with his view of computers as a powerful medium for creating contexts for constructing knowledge: microworlds.

Microworlds are interactive learning environments. Basically, a microworld is a conceptual model of some aspect of the real world. It is usually an idealized and simplified environment, based in a computer or other medium, in which learners (usually children) explore or manipulate the logic, rules, or relationships of the modeled concept, as determined by the designer. A microworld is a cognitive tool.

Although Papert’s microworlds were dedicated to children, we think that computer microworlds might be also helpful to programmers. As Leo Brodie describes in his great book Thinking Forth:

Programming computers can be crazy-making. Other professions give you the luxury of seeing tangible proof of your efforts. A watchmaker can watch the cogs and wheels; a seamstress can watch the seasm come together with each stich. But programmers design, build, and repair the stuff of imagination, ghostly mechanisms that escape the senses. Our work takes place not in RAM, not in an editor, but within our own minds.

Building models in our mind is a very challenging task, so who could need more than developers designing new media for reasoning about these elusive models?

If we apply Engelbart’s view —in which computers are a mean to change and expand human thought— to the software libraries development then we should conceive a software library as a domain-specific “microworld” allowing constructivist explorations, instead of a rigidly directed instructivism.

Once we understand that software libraries —and by extension any software— should be designed consciously as new media for thought, we should answer the question “what makes a good software library? incorporating new features like interactive tutorials, custom visualizations or custom tools like playgrounds, inspectors, debuggers, etc.

As Andrei Chis has predicted we should avoid those libraries that does not satisfy this new requirement:

In today’s world, we avoid libraries with zero tests. In tomorrow’s world, we should avoid libraries that come with zero IDE extensions.

— Andrei Chiș (@Chis_Andrei) August 23, 2017

Moldable development

To put these ideas into practice we need to consider the economics of building these extensions. Fortunately GToolkit, built on top of Pharo, provides a moldable development environment, so that the programmer can adapt the tools to the current needs, easily and frequently.

You can learn more about this fundamentally new perspective on programming called moldable development in the following talk by Tudor Gîrba, who initiated the work on Glamorous Toolkit.

The Glamorous Toolkit offers tools such as an inspector, debugger or a search interface, that are highly moldable in that they can be customized to various contexts.

As Gîrba affirms:

These tools can be customized live with very little effort. The low moldability cost, and we often talk about minutes to adapt the tools, opens new ways to approach understanding code and runtime through live objects.

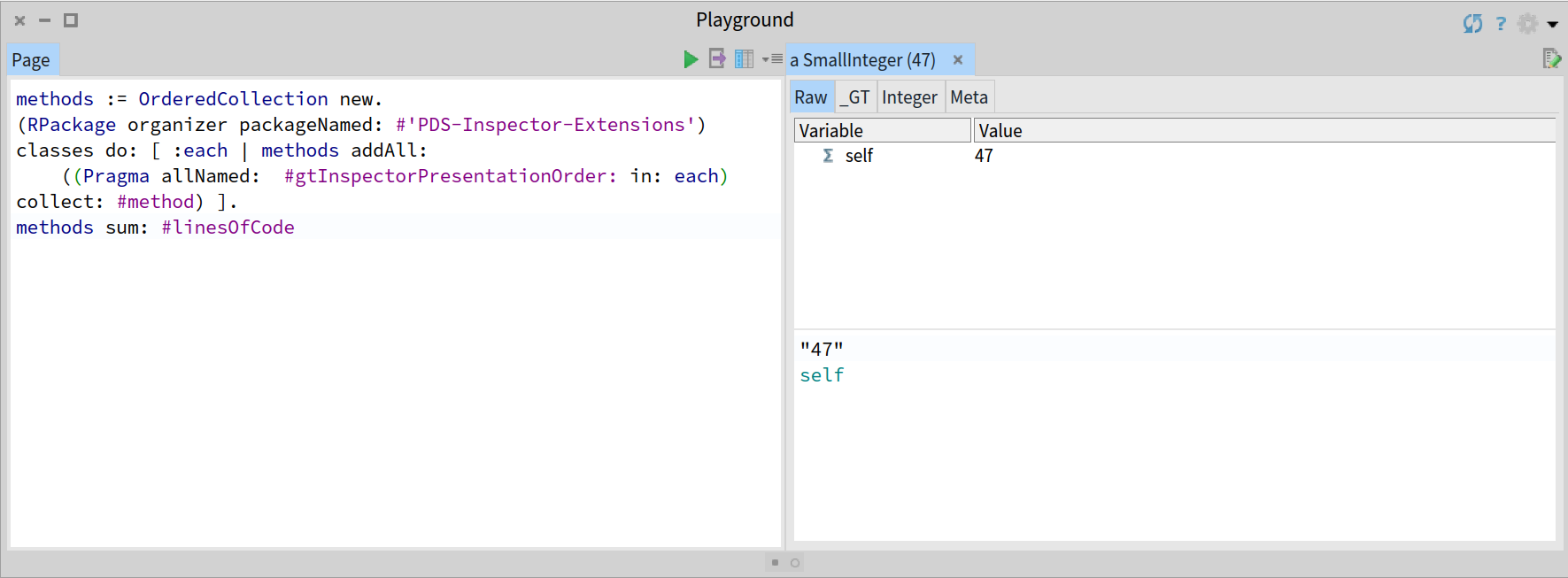

For instance, the Inspector extensions we have developed in our prototype have required only 47 lines of code:

Introspective code to compute the LoC used by custom Inspector extensions of PharoPDS

With PharoPDS we have designed a very rough prototype of a particular type of media for thought, namely, the design of media to understand probabilistic data structures.

We think of this prototype as one of the first steps of a promising journey of creation of more Pharo libraries and tools aligned with Engelbart’s and Papert’s visions.

While most of mainstream libraries and frameworks are running out in a mad rush about implementation details like the startup time:

PetClinic with @micronautfw runs as @graalvm native image. It only takes 300ms to start compared with JAR's 5s. It isn't just a Hello World but it uses JPA/Hibernate/PostgreSQL & Thymeleaf!

— mitz (@bufferings) May 6, 2019

"Micronaut PetClinic" https://t.co/3CMzvfwJju

We think Pharo and Glamorous Toolkit meet the conditions to build a constructionist refuge in the inherently anti-constructionist software industry.

References

- Symourt Papert, Mindstorms: children, computers, and powerful ideas (1980).

- Michael Nielsen, Thought as a Technology (2016).

- Carter & Nielsen, Using Artificial Intelligence to Augment Human Intelligence, Distill, 2017.

- Andrei Chis, Playing with Face Detection in Pharo (2018).

- Andrei Chis’s PhD, Moldable Tools (2016).

- Future of Coding podcast - Episode #36: Moldable Development: Tudor Gîrba (2019).

Credits

- Header photo: Photo by stevepb from pixaby.com with Pixabay License.